What confession does Usher make to the narrator during the final storm?

The Fall of the House of Usher

De Béranger.

Son cœur est un luth suspendu;

Sitôt qu'on le touche il rèsonne.

During the whole of a irksome, dark, and soundless solar day in the autumn of the twelvemonth, when the clouds hung oppressively depression in the heavens, I had been passing lone, on horseback, through a singularly dreary tract of state; and at length found myself, as the shades of the evening drew on, within view of the melancholy House of Conductor. I know non how it was — but, with the first glimpse of the building, a sense of insufferable gloom pervaded my spirit. I say insufferable; for the feeling was unrelieved past any of that half-pleasurable, because poetic, sentiment, with which the listen normally receives even the sternest natural images of the desolate or terrible. I looked upon the scene earlier me — upon the mere house, and the simple landscape features of the domain — upon the bleak walls — upon the vacant centre-like windows — upon a few rank sedges — and upon a few white trunks of decayed trees — with an utter depression of soul which I tin can compare to no earthly sensation more properly than to the subsequently-dream of the reveller upon opium — the bitter lapse into every-day life — the hideous dropping off of the veil. There was an iciness, a sinking, a sickening of the centre — an unredeemed dreariness of thought which no goading of the imagination could torture into nix of the sublime. What was it — I paused to think — what was it that then unnerved me in the contemplation of the House of Usher? It was a mystery all insoluble; nor could I grapple with the shadowy fancies that crowded upon me as I pondered. I was forced to fall dorsum upon the unsatisfactory decision, that while, across uncertainty, at that place are combinations of very elementary natural objects which have the power of thus affecting us, even so the assay of this ability lies among considerations beyond our depth. It was possible, I reflected, that a mere different arrangement of the particulars of the scene, of the details of the motion picture, would be sufficient to modify, or perhaps to demolish its capacity for sorrowful impression; and, interim upon this idea, I reined my horse to the precipitous brink of a black and lurid tarn that lay in unruffled lustre past the domicile, and gazed down — merely with a shudder even more than thrilling than before — upon the re-modelled and inverted images of the grayness sedge, and the ghastly tree-stems, and the vacant and eye-like windows.

Nevertheless, in this mansion of gloom I now proposed to myself a sojourn of some weeks. Its proprietor, Roderick Conductor, had been one of my boon companions in boyhood; but many years had elapsed since our last coming together. A letter of the alphabet, however, had lately reached me in a afar role of the country — a letter of the alphabet from him — which, in its wildly importunate nature, had admitted of no other than a personal reply. The MS. gave evidence of nervous agitation. The author spoke of acute bodily illness — of a mental disorder which oppressed him — and of an earnest desire to meet me, as his all-time, and indeed his merely personal friend, with a view of attempting, past the cheerfulness of my club, some alleviation of his malady. It was the manner in which all this, and much more, was said — it was the apparentcenter that went with his request — which allowed me no room for hesitation; and I accordingly obeyed forthwith what I still considered a very singular summons.

Although, as boys, nosotros had been even intimate assembly, yet I really knew trivial of my friend. His reserve had been always excessive and habitual. I was enlightened, nevertheless, that his very ancient family had been noted, time out of mind, for a peculiar sensibility of temperament, displaying itself, through long ages, in many works of exalted art, and manifested, of tardily, in repeated deeds of munificent notwithstanding unobtrusive charity, likewise as in a passionate devotion to the intricacies, perhaps fifty-fifty more than to the orthodox and easily recognisable beauties, of musical scientific discipline. I had learned, too, the very remarkable fact, that the stem of the Usher race, all time-honored as it was, had put forth, at no period, any enduring co-operative; in other words, that the unabridged family lay in the direct line of descent, and had always, with very trifling and very temporary variation, so lain. It was this deficiency, I considered, while running over in thought the perfect keeping of the graphic symbol of the premises with the accredited character of the people, and while speculating upon the possible influence which the one, in the long lapse of centuries, might take exercised upon the other — it was this deficiency, perchance, of collateral result, and the consequent undeviating transmission, from sire to son, of the patrimony with the name, which had, at length, so identified the two as to merge the original title of the manor in the quaint and equivocal appellation of the "Firm of Conductor" — an appellation which seemed to include, in the minds of the peasantry who used information technology, both the family and the family mansion.

I have said that the sole issue of my somewhat kittenish experiment — that of looking downwards within the tarn — had been to deepen the first singular impression. There tin can exist no incertitude that the consciousness of the rapid increase of my superstition — for why should I not so term it? — served mainly to advance the increase itself. Such, I have long known, is the paradoxical law of all sentiments having terror as a basis. And it might have been for this reason just, that, when I again uplifted my eyes to the house itself, from its image in the pool, there grew in my mind a strange fancy — a fancy so ridiculous, indeed, that I but mention it to show the brilliant forcefulness of the sensations which oppressed me. I had then worked upon my imagination every bit really to believe that about the whole mansion and domain at that place hung an temper peculiar to themselves and their immediate vicinity — an temper which had no affinity with the air of sky, simply which had reeked up from the rust-covered copse, and the gray wall, and the silent tarn — a pestilent and mystic vapor, dull, sluggish, faintly discernible, and leaden-hued.

Shaking off from my spirit whatmust take been a dream, I scanned more than narrowly the real aspect of the building. Its main feature seemed to exist that of an excessive antiquity.[ The discoloration of ages had been nifty. Infinitesimal fungi overspread the whole outside, hanging in a fine tangled spider web-work from the eaves. However all this was autonomously from any extraordinary dilapidation. No portion of the masonry had fallen; and in that location appeared to exist a wild inconsistency between its still perfect accommodation of parts, and the crumbling condition of the individual stones. In this there was much that reminded me of the specious totality of old wood-work which has rotted for long years in some neglected vault, with no disturbance from the jiff of the external air. Beyond this indication of extensive decay, however, the fabric gave little token of instability. Mayhap the eye of a scrutinizing observer might have discovered a barely perceptible fissure, which, extending from the roof of the building in front end, fabricated its style downwardly the wall in a zigzag direction, until it became lost in the sullen waters of the tarn.

Noticing these things, I rode over a short causeway to the firm. A servant in waiting took my horse, and I entered the Gothic archway of the hall. A valet, of stealthy footstep, thence conducted me, in silence, through many dark and intricate passages in my progress to thestudio of his master. Much that I encountered on the way contributed, I know not how, to heighten the vague sentiments of which I take already spoken. While the objects around me — while the carvings of the ceilings, the sombre tapestries of the walls, the ebon black of the floors, and the phantasmagoric armorial trophies which rattled as I strode, were only matters to which, or to such every bit which, I had been accepted from my infancy — while I hesitated non to acknowledge how familiar was all this — I however wondered to find how unfamiliar were the fancies which ordinary images were stirring upwardly. On one of the staircases, I met the doctor of the family. His countenance, I idea, wore a mingled expression of depression cunning and perplexity. He accosted me with trepidation and passed on. The valet now threw open a door and ushered me into the presence of his master.

The room in which I establish myself was very large and lofty. The windows were long, narrow, and pointed, and at so vast a distance from the black oaken floor as to exist altogether inaccessible from within. Feeble gleams of encrimsoned light fabricated their way through the trellissed panes, and served to render sufficiently singled-out the more than prominent objects around; the middle, however, struggled in vain to accomplish the remoter angles of the chamber, or the recesses of the vaulted and fretted ceiling. Dark draperies hung upon the walls. The general piece of furniture was profuse, comfortless, antique, and tattered. Many books and musical instruments lay scattered about, but failed to give any vitality to the scene. I felt that I breathed an temper of sorrow. An air of stern, deep, and irredeemable gloom hung over and pervaded all.

Upon my entrance, Conductor arose from a sofa on which he had been lying at full length, and greeted me with a vivacious warmth which had much in information technology, I at first thought, of an overdone cordiality — of the constrained endeavour of theennuyé homo of the globe. A glance, yet, at his countenance, convinced me of his perfect sincerity. Nosotros sat down; and for some moments, while he spoke not, I gazed upon him with a feeling half of compassion, half of awe. Surely, homo had never before so terribly altered, in so brief a period, equally had Roderick Usher! It was with difficulty that I could bring myself to admit the identity of the wan beingness before me with the companion of my early boyhood. Yet the character of his face had been at all times remarkable. A cadaverousness of complexion; an middle big, liquid, and luminous beyond comparing; lips somewhat sparse and very pallid, but of a surpassingly beautiful curve; a nose of a delicate Hebrew model, but with a breadth of nostril unusual in like formations; a finely moulded chin, speaking, in its want of prominence, of a want of moral energy; hair of a more than than web-like softness and tenuity; these features, with an inordinate expansion above the regions of the temple, made upward birthday a countenance not easily to be forgotten. And now in the mere exaggeration of the prevailing character of these features, and of the expression they were wont to convey, lay so much of change that I doubted to whom I spoke. The at present ghastly pallor of the skin, and the now miraculous lustre of the eye, higher up all things startled and even awed me. The silken hair, too, had been suffered to grow all unheeded, and every bit, in its wild gossamer texture, it floated rather than vicious about the[face, I could not, even with endeavour, connect its Arabesque expression with any idea of simple humanity.

In the way of my friend I was at once struck with an incoherence — an inconsistency; and I shortly found this to arise from a series of feeble and futile struggles to overcome an habitual trepidancy — an excessive nervous agitation. For something of this nature I had indeed been prepared, no less by his letter, than by reminiscences of certain adolescent traits, and by conclusions deduced from his peculiar concrete conformation and temperament. His activity was alternately vivacious and sullen. His voice varied rapidly from a tremulous indecision (when the animal spirits seemed utterly in abeyance) to that species of energetic concision — that abrupt, weighty, unhurried, and hollow-sounding enunciation — that leaden, self-balanced and perfectly modulated guttural utterance, which may be observed in the lost drunk, or the irreclaimable eater of opium, during the periods of his most intense excitement.

It was thus that he spoke of the object of my visit, of his earnest want to come across me, and of the solace he expected me to beget him. He entered, at some length, into what he conceived to be the nature of his malady. It was, he said, a constitutional and a family evil, and one for which he despaired to discover a remedy — a mere nervous affection, he immediately added, which would undoubtedly presently pass off. Information technology displayed itself in a host of unnatural sensations. Some of these, as he detailed them, interested and bewildered me; although, perhaps, the terms, and the full general fashion of the narration had their weight. He suffered much from a morbid affectibility of the senses; the well-nigh insipid food was solitary endurable; he could wear but garments of certain texture; the odors of all flowers were oppressive; his optics were tortured by even a faint light; and there were but peculiar sounds, and these from stringed instruments, which did not inspire him with horror.

To an anomalous species of terror I found him a bounden slave. "I shall perish," said he, "Imust perish in this deplorable folly. Thus, thus, and not otherwise, shall I be lost. I dread the events of the future, not in themselves, but in their results. I shudder at the thought of whatever, fifty-fifty the nigh trivial, incident, which may operate upon this intolerable agitation of soul. I have, indeed, no abhorrence of danger, except in its accented upshot — in terror. In this unnerved — in this pitiable condition — I feel that the period volition sooner or subsequently arrive when I must carelessness life and reason together, in some struggle with the grim phantasm, Fearfulness."

I learned, moreover, at intervals, and through broken and equivocal hints, another singular characteristic of his mental status. He was enchained by certain superstitious impressions in regard to the domicile which he tenanted, and whence, for many years, he had never ventured forth — in regard to an influence whose supposititious force was conveyed in terms too shadowy here to be re-stated — an influence which some peculiarities in the mere class and substance of his family unit mansion, had, by dint of long sufferance, he said, obtained over his spirit — an effect which thephysique of the gray walls and turrets, and of the dim tarn into which they all looked downwards, had, at length, brought about upon themorale of his existence.

He admitted, nonetheless, although with hesitation, that much of the peculiar gloom which thus affected him could exist traced to a more natural and far more palpable origin — to the severe and long-continued illness — indeed to the evidently budgeted dissolution — of a tenderly beloved sis — his sole companion for long years — his last and simply relative on earth. "Her decease," he said, with a bitterness which I tin can never forget, "would leave him (him the hopeless and the frail) the final of the ancient race of the Ushers." While he spoke, the lady Madeline (for so was she called) passed slowly through a remote portion of the apartment, and, without having noticed my presence, disappeared. I regarded her with an utter astonishment not unmingled with dread — and withal I found it impossible to account for such feelings. A sensation of stupor oppressed me, as my eyes followed her retreating steps. When a door, at length, closed upon her, my glance sought instinctively and eagerly the eyebrow of the blood brother — but he had buried his face in his easily, and I could merely perceive that a far more than ordinary wanness had overspread the emaciated fingers through which trickled many passionate tears.

The disease of the lady Madeline had long baffled the skill of her physicians. A settled apathy, a gradual wasting away of the person, and frequent although transient affections of a partially cataleptical grapheme, were the unusual diagnosis. Hitherto she had steadily borne up against the force per unit area of her malady, and had not betaken herself finally to bed; but, on the closing in of the evening of my arrival at the business firm, she succumbed (equally her brother told me at night with inexpressible agitation) to the prostrating power of the destroyer; and I learned that the glimpse I had obtained of her person would thus probably be the terminal I should obtain — that the lady, at to the lowest degree while living, would be seen by me no more.

For several days ensuing, her name was unmentioned by either Conductor or myself: and during this flow I was busied in earnest endeavors to convalesce the melancholy of my friend. We painted and read together; or I listened, every bit if in a dream, to the wild improvisations of his speaking guitar. And thus, equally a closer and however closer intimacy admitted me more unreservedly into the recesses of his spirit, the more bitterly did I perceive the futility of all attempt at auspicious a mind from which darkness, as if an inherent positive quality, poured forth upon all objects of the moral and physical universe, in one unceasing radiation of gloom.

I shall always bear about me a retention of the many solemn hours I thus spent alone with the main of the Business firm of Usher. Nevertheless I should fail in whatever attempt to convey an idea of the exact graphic symbol of the studies, or of the occupations, in which he involved me, or led me the fashion. An excited and highly distempered ideality threw a sulphureous lustre over all. His long improvised dirges will ring forever in my ears. Amidst other things, I hold painfully in heed a certain singular perversion and amplification of the wild air of the last waltz of Von Weber. From the paintings over which his elaborate fancy brooded, and which grew, touch by impact, into vaguenesses at which I shuddered the more thrillingly, because I shuddered knowing non why; — from these paintings (vivid as their images now are before me) I would in vain endeavour to educe more than a minor portion which should lie inside the compass of just written words. By the utter simplicity, past the nakedness of his designs, he arrested and overawed attention. If always mortal painted an thought, that mortal was Roderick Usher. For me at to the lowest degree — in the circumstances then surrounding me — there arose out of the pure abstractions which the hypochondriac contrived to throw upon his sail, an intensity of intolerable awe, no shadow of which felt I e'er yet in the contemplation of the certainly glowing yet too physical reveries of Fuseli.

I of the phantasmagoric conceptions of my friend, partaking not so rigidly of the spirit of brainchild, may be shadowed forth, although feebly, in words. A small moving picture presented the interior of an immensely long and rectangular vault or tunnel, with low walls, smooth, white, and without suspension or device. Certain accessory points of the blueprint served well to convey the idea that this excavation lay at an exceeding depth beneath the surface of the world. No outlet was observed in any portion of its vast extent, and no torch, or other artificial source of light was discernible; yet a flood of intense rays rolled throughout, and bathed the whole in a ghastly and inappropriate splendor.

I accept just spoken of that morbid condition of the auditory nerve which rendered all music intolerable to the sufferer, with the exception of certain effects of stringed instruments. It was, perhaps, the narrow limits to which he thus confined himself upon the guitar, which gave birth, in swell measure, to the fantastic character of his performances. Just the fervidfacility of hisimpromptus could not be then accounted for. They must take been, and were, in the notes, as well as in the words of his wild fantasias (for he non unfrequently accompanied himself with rhymed exact improvisations), the outcome of that intense mental collectedness and concentration to which I have previously alluded as observable only in item moments of the highest artificial excitement. The words of ane of these rhapsodies I have hands remembered. I was, perhaps, the more forcibly impressed with information technology, as he gave it, because, in the under or mystic current of its meaning, I fancied that I perceived, and for the kickoff fourth dimension, a total consciousness on the part of Conductor, of the tottering of his lofty reason upon her throne. The verses, which were entitled "The Haunted Palace," ran very nearly, if non accurately, thus:

I.

In the greenest of our valleys,

By proficient angels tenanted,

Once a fair and stately palace —

Radiant palace — reared its caput.

In the monarch Thought's dominion —

Information technology stood there!

Never seraph spread a pinion

Over fabric half so fair.

II.

Banners yellow, glorious, golden,

On its roof did float and flow;

(This — all this — was in the olden

Time long agone)

And every gentle air that dallied,

In that sweet mean solar day,

Along the ramparts plumed and pallid,

A winged odor went away.

3.

Wanderers in that happy valley

Through 2 luminous windows saw

Spirits moving musically

To a lute'south well-tunéd law,

Round well-nigh a throne, where sitting

(Porphyrogene!)

In state his glory well befitting,

The ruler of the realm was seen.

4.

And all with pearl and reddish glowing

Was the fair palace door,

Through which came flowing, flowing, flowing,

And sparkling evermore,

A troop of Echoes whose sugariness duty

Was only to sing,

In voices of surpassing beauty,

The wit and wisdom of their king.

V.

But evil things, in robes of sorrow,

Assailed the monarch's high estate;

(Ah, allow united states mourn, for never morrow

Shall dawn upon him, desolate!)

And, round about his habitation, the glory

That blushed and bloomed

Is but a dim-remembered story

Of the one-time time entombed.

Six.

And travellers now within that valley,

Through the red-litten windows, see

Vast forms that move fantastically

To a discordant melody;

While, similar a rapid ghastly river,

Through the pale door,

A hideous throng blitz out forever,

And express joy — but smiling no more.

I well remember that suggestions arising from this ballad, led u.s.a. into a train of thought wherein in that location became manifest an opinion of Usher'southward which I mention not so much on account of its novelty, (for other men accept thought thus,) as on business relationship of the pertinacity with which he maintained it. This opinion, in its general course, was that of the sentience of all vegetable things. But, in his disordered fancy, the idea had causeless a more daring character, and trespassed, under certain atmospheric condition, upon the kingdom of inorganization. I lack words to limited the full extent, or the earnest abandon of his persuasion. The conventionalities, withal, was connected (as I have previously hinted) with the grey stones of the home of his forefathers. The conditions of the sentience had been here, he imagined, fulfilled in the method of collocation of these stones — in the order of their arrangement, equally well as in that of the manyfungi which overspread them, and of the decayed trees which stood around — higher up all, in the long undisturbed endurance of this organisation, and in its reduplication in the still waters of the tarn. Its testify — the evidence of the sentience — was to be seen, he said, (and I here started every bit he spoke,) in the gradual yet certain condensation of an atmosphere of their ain nearly the waters and the walls. The result was discoverable, he added, in that silent, yet importunate and terrible influence which for centuries had moulded the destinies of his family, and which madehim what I at present saw him — what he was. Such opinions need no comment, and I volition make none.

Our books — the books which, for years, had formed no modest portion of the mental existence of the invalid — were, as might be supposed, in strict keeping with this character of phantasm. We pored together over such works as the Ververt et Chartreuse of Gresset; the Belphegor of Machiavelli; the Heaven and Hell of Swedenborg; the Subterranean Voyage of Nicholas Klimm by Holberg; the Chiromancy of Robert Flud, of Jean D'Indaginé, and of De la Chambre; the Journeying into the Blue Altitude of Tieck; and the Urban center of the Sun of Campanella. I favorite book was a small octavo edition of theDirectorium Inquisitorium , past the Dominican Eymeric de Gironne; and there were passages in Pomponius Mela, nearly the old African Satyrs and œgipans, over which Usher would sit dreaming for hours. His primary delight, however, was found in the perusal of an exceedingly rare and curious book in quarto Gothic — the manual of a forgotten church — theVigiliae Mortuorum secundum Chorum Ecclesiae Maguntinae.

I could not aid thinking of the wild ritual of this work, and of its likely influence upon the hypochondriac, when, i evening, having informed me abruptly that the lady Madeline was no more, he stated his intention of preserving her corpse for a fortnight, (previously to its last interment,) in 1 of the numerous vaults inside the primary walls of the building. The worldly reason, however, assigned for this atypical proceeding, was one which I did not feel at freedom to dispute. The brother had been led to his resolution (so he told me) past consideration of the unusual character of the malady of the deceased, of certain obtrusive and eager inquiries on the part of her medical men, and of the remote and exposed situation of the burying-ground of the family. I volition not deny that when I called to mind the sinister countenance of the person whom I met upon the staircase, on the day of my arrival at the house, I had no desire to oppose what I regarded equally at best simply a harmless, and by no means an unnatural, precaution.

At the request of Usher, I personally aided him in the arrangements for the temporary entombment. The body having been encoffined, we two alone diameter information technology to its rest. The vault in which nosotros placed it (and which had been so long unopened that our torches, one-half smothered in its oppressive atmosphere, gave u.s. little opportunity for investigation) was small-scale, damp, and entirely without means of admission for light; lying, at great depth, immediately below that portion of the building in which was my own sleeping apartment. It had been used, apparently, in remote feudal times, for the worst purposes of a donjon-go on, and, in subsequently days, every bit a identify of deposit for pulverization, or some other highly combustible substance, as a portion of its flooring, and the whole interior of a long archway through which we reached it, were carefully sheathed with copper. The door, of massive iron, had been, also, similarly protected. Its immense weight caused an unusually sharp grating sound, as it moved upon its hinges.

Having deposited our mournful burden upon tressels inside this region of horror, we partially turned aside the even so unscrewed chapeau of the coffin, and looked upon the face of the tenant. A striking similitude betwixt the brother and sister at present outset arrested my attention; and Usher, divining, perchance, my thoughts, murmured out some few words from which I learned that the deceased and himself had been twins, and that sympathies of a scarcely intelligible nature had always existed between them. Our glances, all the same, rested not long upon the dead — for we could not regard her unawed. The illness which had thus entombed the lady in the maturity of youth, had left, as usual in all maladies of a strictly cataleptical character, the mockery of a faint blush upon the bosom and the face, and that suspiciously lingering smile upon the lip which is so terrible in death. Nosotros replaced and screwed downward the lid, and, having secured the door of iron, fabricated our fashion, with toil, into the scarcely less gloomy apartments of the upper portion of the business firm.

And at present, some days of bitter grief having elapsed, an appreciable change came over the features of the mental disorder of my friend. His ordinary style had vanished. His ordinary occupations were neglected or forgotten. He roamed from bedroom to bedroom with hurried, unequal, and objectless step. The pallor of his countenance had assumed, if possible, a more ghastly hue — but the luminousness of his center had utterly gone out. The once occasional huskiness of his tone was heard no more; and a tremulous quaver, every bit if of extreme terror, habitually characterized his utterance. In that location were times, indeed, when I thought his unceasingly agitated heed was laboring with some oppressive hole-and-corner, to divulge which he struggled for the necessary courage. At times, again, I was obliged to resolve all into the mere inexplicable vagaries of madness, for I beheld him gazing upon vacancy for long hours, in an attitude of the profoundest attention, equally if listening to some imaginary audio. It was no wonder that his condition terrified — that it infected me. I felt creeping upon me, by deadening all the same sure degrees, the wild influences of his own fantastic notwithstanding impressive superstitions.

It was, peculiarly, upon retiring to bed late in the night of the seventh or eighth twenty-four hours subsequently the placing of the lady Madeline within the donjon, that I experienced the total power of such feelings. Sleep came non most my couch — while the hours waned and waned abroad. I struggled to reason off the nervousness which had rule over me. I endeavored to believe that much, if not all of what I felt, was due to the bewildering influence of the gloomy article of furniture of the room — of the dark and tattered draperies, which, tortured into motility by the breath of a rising storm, swayed fitfully to and fro upon the walls, and rustled uneasily nigh the decorations of the bed. Merely my efforts were fruitless. An irrepressible tremor gradually pervaded my frame; and, at length, in that location sat upon my very centre an incubus of utterly causeless alert. Shaking this off with a gasp and a struggle, I uplifted myself upon the pillows, and, peering earnestly within the intense darkness of the chamber, harkened — I know not why, except that an instinctive spirit prompted me — to certain low and indefinite sounds which came, through the pauses of the storm, at long intervals, I knew not whence. Overpowered by an intense sentiment of horror, unaccountable yet unendurable, I threw on my clothes with haste (for I felt that I should sleep no more than during the nighttime), and endeavored to arouse myself from the pitiable status into which I had fallen, by pacing speedily to and fro through the apartment.

I had taken but few turns in this manner, when a light pace on an adjoining staircase arrested my attention. I presently recognised information technology as that of Usher. In an instant subsequently he rapped,[with a gentle touch on, at my door, and entered, bearing a lamp. His countenance was, as usual, cadaverously wan — simply, moreover, there was a species of mad hilarity in his optics — an plain restrainedhysteria in his whole demeanor. His air appalled me — merely annihilation was preferable to the solitude which I had so long endured, and I even welcomed his presence as a relief.

"And you take not seen it?" he said abruptly, subsequently having stared about him for some moments in silence — "you have non then seen it? — but, stay! you shall." Thus speaking, and having carefully shaded his lamp, he hurried to 1 of the casements, and threw it freely open to the storm.

The impetuous fury of the inbound gust nearly lifted us from our anxiety. It was, indeed, a tempestuous yet sternly beautiful night, and 1 wildly singular in its terror and its beauty. A whirlwind had plain collected its force in our vicinity; for there were frequent and trigger-happy alterations in the direction of the air current; and the exceeding density of the clouds (which hung so depression as to printing upon the turrets of the business firm) did not prevent our perceiving the life-similar velocity with which they flew careering from all points against each other, without passing away into the altitude. I say that even their exceeding density did not preclude our perceiving this — withal we had no glimpse of the moon or stars — nor was at that place any flashing forth of the lightning. But the under surfaces of the huge masses of agitated vapor, as well as all terrestrial objects immediately effectually u.s., were glowing in the unnatural light of a faintly luminous and distinctly visible gaseous exhalation which hung about and enshrouded the mansion.

"Y'all must not — yous shall not behold this!" said I, shudderingly, to Usher, every bit I led him, with a gentle violence, from the window to a seat. "These appearances, which bewilder you, are simply electrical phenomena not uncommon — or information technology may be that they have their ghastly origin in the rank miasma of the tarn. Let us close this casement; — the air is spooky and dangerous to your frame. Here is one of your favorite romances. I will read, and you shall listen; — and so we will laissez passer away this terrible night together."

The antiquarian book which I had taken up was the "Mad Trist" of Sir Launcelot Canning; but I had chosen it a favorite of Usher'due south more in sad jest than in hostage; for, in truth, in that location is little in its uncouth and unimaginative prolixity which could have had interest for the lofty and spiritual ideality of my friend. It was, however, the only book immediately at paw; and I indulged a vague promise that the excitement which now agitated the hypochondriac, might find relief (for the history of mental disorder is total of similar anomalies) even in the extremeness of the folly which I should read. Could I have judged, indeed, by the wild overstrained air of vivacity with which he harkened, or apparently harkened, to the words of the tale, I might well have congratulated myself upon the success of my design.

I had arrived at that well-known portion of the story where Ethelred, the hero of the Trist, having sought in vain for peaceable access into the abode of the hermit, proceeds to make good an entrance past force. Here, it will exist remembered, the words of the narrative run thus:

"And Ethelred, who was by nature of a doughty center, and who was now mighty nonetheless, on business relationship of the powerfulness of the wine which he had drunken, waited no longer to concord parley with the hermit, who, in sooth, was of an obstinate and maliceful turn, simply, feeling the pelting upon his shoulders, and fearing the rising of the storm, uplifted his mace outright, and, with blows, made chop-chop room in the plankings of the door for his gauntleted hand; and at present pulling therewith sturdily, he so cracked, and ripped, and tore all asunder, that the noise of the dry out and hollow-sounding forest alarummed and reverberated throughout the forest."

At the termination of this judgement I started, and for a moment, paused; for it appeared to me (although I at once ended that my excited fancy had deceived me) — it appeared to me that, from some very remote portion of the mansion, at that place came, indistinctly, to my ears, what might accept been, in its verbal similarity of grapheme, the echo (but a stifled and ho-hum i certainly) of the very cracking and ripping audio which Sir Launcelot had so particularly described. It was, beyond doubt, the coincidence alone which had arrested my attention; for, among the rattling of the sashes of the casements, and the ordinary commingled noises of the still increasing storm, the sound, in itself, had nothing,[surely, which should have interested or disturbed me. I continued the story:

"But the proficient champion Ethelred, now entering within the door, was sore enraged and amazed to perceive no point of the maliceful hermit; only, in the stead thereof, a dragon of a scaly and prodigious demeanor, and of a fiery tongue, which sate in guard before a palace of gold, with a floor of silver; and upon the wall there hung a shield of shining brass with this fable enwritten —

Who entereth herein, a conquistador hath bin;

Who slayeth the dragon, the shield he shall win;

And Ethelred uplifted his mace, and struck upon the head of the dragon, which barbarous before him, and gave up his pesty breath, with a shriek so horrid and harsh, and however and so piercing, that Ethelred had fain to close his ears with his hands against the dreadful racket of it, the like whereof was never earlier heard."

Hither again I paused abruptly, and now with a feeling of wild anaesthesia — for in that location could be no uncertainty whatever that, in this case, I did really hear (although from what direction it proceeded I found it incommunicable to say) a low and apparently afar, but harsh, protracted, and most unusual screaming or grating sound — the verbal counterpart of what my fancy had already conjured up for the dragon's unnatural shriek equally described by the romancer.

Oppressed, equally I certainly was, upon the occurrence of this second and most boggling coincidence, past a thousand conflicting sensations, in which wonder and extreme terror were predominant, I withal retained sufficient presence of mind to avoid heady, by any ascertainment, the sensitive nervousness of my companion. I was past no means certain that he had noticed the sounds in question; although, convincingly, a strange amending had, during the last few minutes, taken place in his demeanor. From a position fronting my ain, he had gradually brought round his chair, so equally to sit down with his confront to the door of the sleeping accommodation; and thus I could but partially perceive his features, although I saw that his lips trembled equally if he were murmuring inaudibly. His head had dropped upon his breast — yet I knew that he was not[asleep, from the broad and rigid opening of the center as I caught a glance of it in contour. The motion of his body, as well, was at variance with this thought — for he rocked from side to side with a gentle all the same constant and uniform sway. Having quickly taken notice of all this, I resumed the narrative of Sir Launcelot, which thus proceeded:

"And now, the champion, having escaped from the terrible fury of the dragon, bethinking himself of the brazen shield, and of the breaking up of the enchantment which was upon it, removed the carcass from out of the way earlier him, and approached valorously over the silver pavement of the castle to where the shield was upon the wall; which in sooth tarried not for his total coming, but savage downward at his anxiety upon the silver floor, with a mighty dandy and terrible ringing sound."

No sooner had these syllables passed my lips, than — as if a shield of contumely had indeed, at the moment, fallen heavily upon a floor of silver — I became aware of a singled-out, hollow, metallic, and clangorous, yet apparently muffled reverberation. Completely unnerved, I leaped to my feet; but the measured rocking move of Usher was undisturbed. I rushed to the chair in which he sat. His eyes were aptitude fixedly before him, and throughout his whole eyebrow there reigned a stony rigidity. Only, as I placed my hand upon his shoulder, there came a strong shudder over his whole person; a sickly smile quivered about his lips; and I saw that he spoke in a low, hurried, and gibbering murmur, as if unconscious of my presence. Bending closely over him, I at length drank in the hideous import of his words.

"Not hear information technology? — yes, I hear it, andhave heard it. Long — long — long — many minutes, many hours, many days, have I heard it — yet I dared non — oh, pity me, miserable wretch that I am! — I dared not — Idared not speak!We have put her living in the tomb! Said I not that my senses were acute? Inow tell you that I heard her first feeble movements in the hollow coffin. I heard them — many, many days ago — yet I dared not —I dared not speak! And now — to-nighttime — Ethelred — ha! ha! — the breaking of the hermit'southward door, and the death-cry of the dragon, and the clangor of the shield! — say, rather, the rending of her bury, and the grating of the fe hinges of her prison, and her struggles within the coppered archway of the vault! Oh whither shall I fly? Will she not be here betimes? Is she not hurrying to upbraid me for my haste? Have I not heard her footstep on the stair? Practise I not distinguish that heavy and horrible chirapsia of her heart? Madman!" — here he sprang furiously to his feet, and shrieked out his syllables, as if in the effort he were giving up his soul — "Madman! I tell you that she now stands without the door!"

Every bit if in the superhuman energy of his utterance there had been found the say-so of a spell — the huge antique pannels to which the speaker pointed, threw slowly back, upon the instant, their ponderous and ebony jaws. It was the work of the rushing gust — but then without those doors theredid stand the lofty and enshrouded figure of the lady Madeline of Conductor. There was claret upon her white robes, and the evidence of some biting struggle upon every portion of her emaciated frame. For a moment she remained trembling and reeling to and fro upon the threshold — then, with a low moaning cry, roughshod heavily inward upon the person of her brother, and in her violent and now final death-agonies, bore him to the floor a corpse, and a victim to the terrors he had anticipated.

From that chamber, and from that mansion, I fled balked. The storm was even so abroad in all its wrath every bit I establish myself crossing the erstwhile causeway. Suddenly there shot forth the path a wild calorie-free, and I turned to see whence a gleam so unusual could take issued; for the vast house and its shadows were alone behind me. The radiance was that of the full, setting, and blood-reddish moon, which now shone vividly through that in one case barely-discernible fissure, of which I have before spoken equally extending from the roof of the building, in a zigzag management, to the base. While I gazed, this fissure apace widened — in that location came a fierce jiff of the cyclone — the entire orb of the satellite burst at one time upon my sight — my brain reeled as I saw the mighty walls rushing asunder — at that place was a long tumultuous shouting sound like the vox of a thousand waters — and the deep and dank tarn at my anxiety closed sullenly and silently over the fragments of the "Business firm of Conductor."

Edgar Allan Poe

Published in 1839

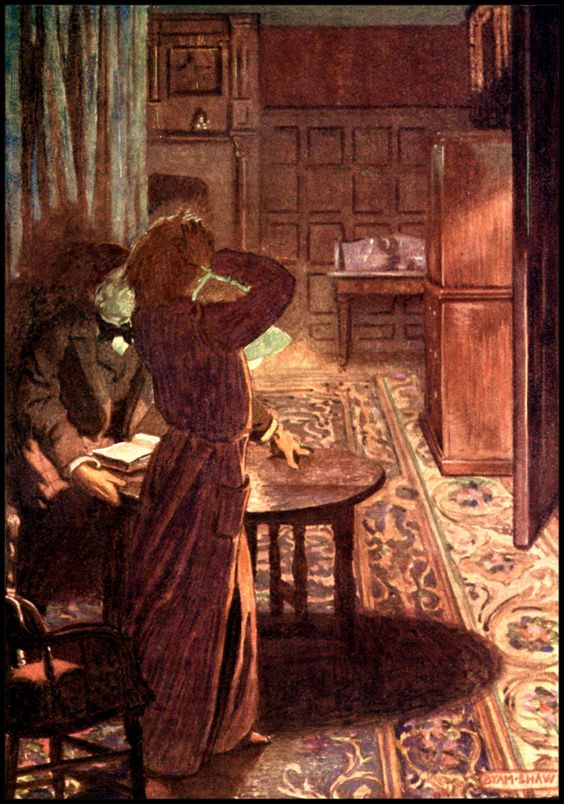

Prototype past Byam Shaw

Source: https://poemuseum.org/the-fall-of-the-house-of-usher/

0 Response to "What confession does Usher make to the narrator during the final storm?"

Post a Comment